|

|

|||||||||||||||||

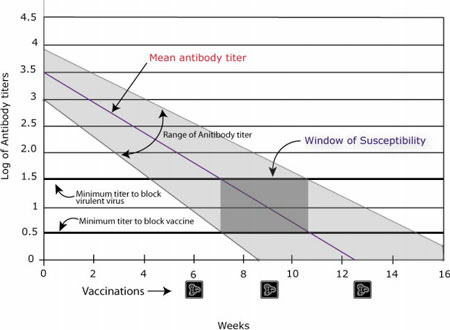

What About Canine VaccinationsVaccination Recommendations (Puppy Shots)The vaccination of puppies (puppy shots) is one of the crucial steps in assuring the puppy will have a healthy and happy puppyhood. The who, what, why, when, where, and how of vaccinations are complicated, and may vary from puppy to puppy. Always consult with your veterinarian to determine which vaccines are appropriate for your puppy. To better understand vaccines, it is important to understand how the puppy is protected from disease the first few weeks of its life. Protection from the mother (maternal antibodies)A newborn puppy is not naturally immune to diseases. However, it does have some antibody protection which is derived from its mother's blood via the placenta. The next level of immunity is from antibodies derived from the first milk. This is the milk produced from the time of birth and continuing for 36-48 hours. This antibody-rich milk is called colostrum. The puppy does not continue to receive antibodies through its mother's milk. It only receives antibodies until it is two days of age. All antibodies derived from the mother, either via her blood or colostrum are called maternal antibodies. It must be noted that the puppy will only receive antibodies against diseases for which the mother had been recently vaccinated against or exposed to. As an example, a mother that had NOT been vaccinated against or exposed to parvovirus, would not have any antibodies against parvovirus to pass along to her puppies. The puppies then would be susceptible to developing a parvovirus infection. Window of susceptibilityThe age at which puppies can effectively be immunized (protected) is proportional to the amount of antibodies the puppy received from its mother. High levels of maternal antibodies present in the puppies' bloodstream will block the effectiveness of a vaccine. When the maternal antibodies drop to a low enough level in the puppy, immunization by a commercial vaccine will work. The antibodies from the mother generally circulate in the newborn's blood for a number of weeks. There is a period of time from several days to several weeks in which the maternal antibodies are too low to provide protection against the disease, but too high to allow a vaccine to work. This period is called the window of susceptibility. This is the time when despite being vaccinated, a puppy or kitten can still contract the disease.

NEW PRINCIPLES OF IMMUNOLOGY"Dogs and cats immune systems mature fully at 6 months. If a modified live virus vaccine is given after 6 months of age, it produces an immunity which is good for the life of the pet (ie: canine distemper, parvo, feline distemper). If another MLV vaccine is given a year later, the antibodies from the first vaccine neutralize the antigens of the second vaccine and there is little or no effect. The titer is not "boosted" nor are more memory cells induced." Not only are annual boosters for parvo and distemper unnecessary, they subject the pet to potential risks of allergic reactions and immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. "There is no scientific documentation to back up label claims for annual administration of MLV vaccines." Puppies receive antibodies through their mothers milk. This natural protection can last 8-14 weeks. Puppies & kittens should NOT be vaccinated at LESS than 8 weeks. Maternal immunity will neutralize the vaccine and little protection (0-38%) will be produced. Vaccination at 6 weeks will, however, delay the timing of the first highly effective vaccine. Vaccinations given 2 weeks apart suppress rather than stimulate the immune system. A series of vaccinations is given starting at 8 weeks and given 3-4 weeks apart up to 16 weeks of age. Another vaccination given sometime after 6 months of age (usually at 1 year 4 mo) WILL PROVIDE LIFETIME IMMUNITY. CURRENT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DOGSDistemper & Parvo "According to Dr. Schultz, AVMA, 8-15-95, when a vaccinations series given at 2, 3 & 4 months and again at 1 year with a MLV, puppies and kitten program memory cells that survive for life, providing lifelong immunity." Dr. Carmichael at Cornell and Dr. Schultz have studies showing immunity against challenge at 2-10 years for canine distemper & 4 years for parvovirus. Studies for longer duration are pending. "There are no new strains of parvovirus as one mfg. would like to suggest. Parvovirus vaccination provides cross immunity for all types." Hepatitis (Adenovirus) is one of the agents known to be a cause of kennel cough. Only vaccines with CAV-2 should be used as CAV-1 vaccines carry the risk of "hepatitis blue-eye" reactions & kidney damage. Bordetella Parainfluenza: Commonly called "Kennel cough" Recommended only for those dogs boarded, groomed, taken to dog shows, or for any reason housed where exposed to a lot of dogs. The intranasal vaccine provides more complete and more rapid onset of immunity with less chance of reaction. Immunity requires 72 hours and does not protect from every cause of kennel cough. Immunity is of short duration (4 to 6 months). VACCINATIONS NOT RECOMMENDEDMultiple components in vaccines compete with each other for the immune system and result in lesser immunity for each individual disease as well as increasing the risk of a reaction. Canine Corona Virus is only a disease of puppies. It is rare, self limiting (dogs get well in 3 days without treatment). Cornell & Texas A&M have only diagnosed one case each in the last 7 years. Corona virus does not cause disease in adult dogs. Leptospirosis vaccine is a common cause of adverse reactions in dogsMost of the clinical cases of lepto reported in dogs in the US are caused by serovaars (or types) grippotyphosa and bratsilvia. The vaccines contain different serovaars eanicola and ictohemorrhagica. Cross protection is not provided and protection is short lived. Lepto vaccine is immuno-supressive to puppies less than 16 weeks. By Karen Dale DustmanKDustman@aol.com Vaccines -- Part I: Move over, politics, religion, and gun control. The latest "hot" topic of debate: can routine vaccinations harm your pet. Even raising the issue may seem a bit like questioning the virtues of motherhood and apple pie. Vaccinations are, after all, among the most prominent weapons in veterinary arsenals today against devastating diseases including rabies, distemper, parvovirus, and leukemia. But then, critics point out, medical science also once considered leeches de rigeur. And more and more holistic practitioners are reporting cases in which they believe over-vaccination may be linked to a wide assortment of veterinary ills. More conventionally-minded health professionals acknowledge that vaccines, like any form of medical intervention, can have side effects in rare instances. But, they say, the benefits of vaccination usually far outweigh the risks. Who's right? Conclusive data isn't in yet, but there seem to be valid points raised by both sides. Here's a look at this thorny but fascinating debate. Trouble in Paradise? For Don Hamilton, D.V.M., a holistic veterinarian in Ocate, New Mexico, the turning point was a Persian cat named Fluffy with a puzzling pattern of repeated urinary tract infections. "I read through her chart and found that for three years in a row, she would come in for her annual vaccination, and about a month later, would be back with a urinary tract infection," explained Dr. Hamilton. Suspecting that Fluffy's annual vaccinations may have played a part in her problem, Dr. Hamilton recommended that the cat not receive further vaccinations. Fluffy has remained infection-free ever since, he noted. Some might call it a coincidence. But for Hamilton, the idea that routine vaccinations may be linked to seemingly unrelated illnesses was a significant insight. "Once you see something like that and say, is it possible, and then look through your cases with the idea that it is possible, then you see a lot of things you didn't see before," Hamilton said. "The trouble is, we're so heavily taught that vaccines are helpful, and if not helpful, that they're at least not harmful. So when you see what I now think are vaccine-related damage, you tend to say it's not possible, and dismiss it." Reports of vaccine-related problems in animals come as no surprise to Dr. Richard Pitcairn, D.V.M., founder of the Academy of Veterinary Homeopathy in Eugene, Oregon, and one of the first to point to a possible correlation between vaccines and other illnesses. "We do see a number of health problems we associate with vaccines, [often] having to do with immune problems or allergies," confirmed Dr. Pitcairn. "It also seems that animals become more susceptible to other infections, so a cat that gets the feline leukemia vaccine might come down a month later with FIP (feline infectious peritonitis). There is some evidence reported in the veterinary literature that after a vaccine, the immune system weakens or the animal is more susceptible to diseases of other sorts." The link between vaccinations and the immune system is cited by other veterinarians as well, although some caution that immune problems may involve more factors than just vaccination. " We're seeing more immune problems in general," noted Jean Dodds, D.V.M. a veterinarian with a referral practice in hematology and immunology in Santa Monica, Cal-ifornia. "And it's likely that vacinations are just one of the triggers in individuals that are susceptible." Many holistic veterinarians also report that their observations in practice seem to support a link between vaccinations and a wide variety of ailments. "You take healthy animals and often very quickly after you vaccinate, you can see simple things like itching of the skin or excessive licking of the paws, sometimes even with no eruptions," said Dee Blanco, D.V.M., a holistic practitioner in Santa Fe, New Mexico. "We see a lot of epilepsy, often after a rabies vaccination. Or dogs or cats can become aggressive for several days. Frequently, you'll see urinary tract infections in cats, often within three months after their [annual] vaccination. If you step back, open your mind and heart, you'll start to see patterns of illness post-vaccination." Vaccinations may even contribute to premature death in animals whose immune systems were already compromised, some veterinarians believe. "I had two situations where we had spent a long time building up two older, severely immunocompromised dogs, and then their owners had them vaccinated for just about everything known to man," recalled Dr. Carvel Tiekert, executive director and founder of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association headquartered in Bel Air, Maryland. "Both of those dogs died within about a month of vaccination. Can we prove a cause and effect? No. Do I think there was a cause and effect? Yes." More Subtle Effects: In addition to -- or perhaps underlying -- the more overt symptoms, some veterinarians believe that vaccination can produce a chronic illness known as "vaccinosis", which leaves the patient less able to fend off other medical problems. "Animals react adversely to vaccines in two main ways. The first is the more obvious immediate anaphylactic response, where the animal may develop swelling of the face or ears, as well as pain and inflammation at the site of inection," said Donna Starita Mehan, D.V.M., a veterinarian in Boring, Oregon. "But a larger number of animals develop an under-current, [a] subtle immune system shift that compounds every time they receive a vaccination. This may later manifest as any number of chronic degenerative illnesses such as arthritis, skin or ear problems, gum or throat inflammation, behav-ior problems, central nervous system disorders (i.e. epilepsy), or cancer." The link between vaccination and disease, however, is an indirect one, explain those who accept the vaccinosis theory. "It is not necessarily that the diseases are caused by the vaccine," emphasized Dr. Blanco. "There are weaknesses inherent in all of us, either from our environment or acquired or inherited tendencies. If you have a family line of diabetes or hip dysplasia or whatever your weak area is, the vaccine will essentially exacerbate the weakness and the animal becomes symptomatic. I think the immune system is finite, and overloading it [with too many vaccinations] is really hard on the system. The immune system says to itself, 'These rabies or other viruses in my body are a life-threatening illness -- I must deal with this,' but there isn't enough energy to also keep everything in balance. Therefore, the weaknesses are expressed." Rabies vaccine, in particular, is frequently linked by holistic veterinarians to adverse changes in dogs' behavior. "What I've seen happen is, after vaccination, dogs develop what we call the 'rabies miasm', where they become more aggressive, more likely to bite, more nervous and suspicious," noted Dr. Pitcairn. "They may also have a tendency to run away, to wander, and also sometimes to have excessive saliva, and to tear things up. It's not that they have rabies, but they seem to express some symptoms of the disease from exposure to the vaccine." Some veterinarians even suggest that illness-es like parvo may be the direct result of well-intentioned vaccination efforts. "Parvo wasn't around until about twenty years ago," Dr. Hamilton noted. "I think parvo resulted because of the distemper vaccination. I've seen cases where a dog tested positive [for parvo], and then within 24 hours it turned and became a full-blown [case of] distemper. Now, conventionally they will tell you the dog was simply harboring both viruses. I don't think so. I think it just shifted, from one to the other." Looking for Links What exactly in a vaccine might promote such adverse reactions? "Vaccine products may contain artificial colors, antibiotics, aluminum, formaldehyde, BHA, and BHT, in addition to the viral antigen," noted Dr. Mehan. "Syncytial viruses inadvertently grown on the same media may also be included as contaminants," she said. Other experts note that most vaccinations introduce a substance directly into body tissues, rather than through the nose or mouth, the normal routes of infection. And there may also be a cumulative impact on the immune system with repeated vaccinations, they say. Even some experts outside the holistic community believe that Americans may be over-vaccinating their pets. "Almost without exception, there is no immunologic requirement for annual revaccination. Immunity to viruses persists for years or for the life of the animal," wrote Ronald D. Schultz, Ph.D., a professor and chair of the department of athobiological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine, who has studied vaccines for nearly 30 years. In a widely-quoted article co-authored with T. Phillips, D.V.M. published in Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy in 1992, Drs. Schultz and Phillips called the practice of annual boosters one of "questionable efficacy." Our own experience with human vaccinations tends to support that idea, notes Christina Chambreau, D.V.M., a veterin-arian with an entirely homeopathic practice in Sparks, Maryland. "How many of us get DPT, polio, tetanus, diptheria -- all the childhood vaccines -- every year?" she asked. "If you don't, why do your animals need them?" Not so fast, caution more conventially-minded veterinarians. There are significant differences between humans and animals -- and between human and animal diseases -- that need to be factored in. "Remember that dogs age 7 times faster than we do," said Roger Schwartz, D.V.M., a clinical research veterinarian with manufacturer Hoechst Roussel Vet in Somerville, New Jersey. "One year for us is the equivalent of a month and a half for a dog. So a yearly booster for them is like a seven-year booster for us." And although annual revaccination may sound a bit like overkill, that's not necessarily the case, some experts emphasize. Manufacturers' label recommendations for the frequency of revaccination are meant to provide guidance for the general population of animals," Beth Bielsker, D.V.M., manager of veterinary affairs for Solvay Animal Health in Mendota Heights, Minnesota. "Are there going to be some animals in which protection lasts longer than a year? Yes, just as here will be animals where protection may be less than a year. It is very difficult to make generalizations in an area where the response to vaccine is very individualized," she said. A number of factors can i nhibit the development of a proper immune response, making repeated vaccinations important to ensure immunity, pointed out Joseph Curlee, D.V.M., a veterinarian with United Vaccines, Inc. in Madison, Wisconsin. "Although animals are 'vaccinated,' it does not infer that they have produced a protective immune response," Dr. Curlee said. "Several factors to consider at the time of vaccination of the animal are stress, pre-existing or incubating disease, poor nutrition, parasitism, immune suppressive diseases or treatments, and age (maternal antibody interference). Anyone of these may result in an inadquate immune response to the vaccine which may require additional vaccinations in order to insure that the animal is protected." And while some may speculate that vaccine companies prefer to market a product that must be readministered every year, it is actually in vaccine companies' own interest to produce longer-lasting vaccines, Dr. Schwartz said. "If a company can sell a product that lasts two years between doses and the others on the market last one year, guess who's going to win the race. There's always a push to lengthen the interval, because that means you have a more potent product." However, even traditional veterinarians agree there may be a limit to the number of vaccinations an animal should receive. "The reality is, yes, a vaccine does cost the animal something -- it costs them a little bit of their metabolic energy to produce a response to that vaccine," observed Dr. Schwartz of Hoechst Roussel. "Animals and people are born with essentially a limitless potential to develop immunological responses to antigens, [but] that 'limitless' part refers to the variety of antigens that the animal can respond to. The animal's metabolic ability has limits. It's like your computer at home -- how many software programs can you put on it? Your hard drive has a certain capacity. If you have only 640 megabytes compared to several gigabytes, for example, you may have to be more selective about what you put on it. But remember, it is the software that makes a computer useful." Tough Tie-Ins: Establishing that an animal's health problems are vaccination-related can be difficult, holistic veterinarians concede. "Those of us in alternative therapy feel strongly that there are such problems, but that is based on in-the-field obser-vation," noted Carolyn Blakey, D.V.M., an alternatives [sic] practitioner in Richmond, Indiana. "The drug manufacturers and most non-alternative veterinarians deny that, because the reactions are delayed -- quite delayed, frequently. So they say, 'Where's the proof that the vaccine did it?' And they have a valid point, of course. But once in a while, often enough that you can put your finger on it, within a few days or a month [after vaccination], you can correlate a deterior-ation in the animal's health." Vaccinations are also only one in a constellation of factors that may affect an animal's health, holistic practitioners emphasize. "I don't want to imply that [vaccination] is the whole cause," cautioned Dr. Pitcairn. "More, it aggravates or makes [an existing condition] worse. Maybe there is an inherited tendency toward allergies, and then along comes the vaccine, or several together. And it's too much." Conventional veterinarians point out, however, that the very frequency of a typical vaccination program makes it easy to mistakenly blame a vaccine. "For pediatric disease, for instance, it's very common in veterinary practice to vaccine puppies on a three- to four- week interval, from the time they are six weeks of age until they are 16 weeks old," pointed out David Hustead, D.V.M., director of professional services for Ft. Dodge Animal Health in Overland Park, Kansas. "Now, if a puppy gets any illness from the time they are six weeks of age to 16 weeks, that illness is within three weeks of the date they got a vaccine. So it is very easy to say it had to be caused by a vaccine." Vaccines may also be inappropriately blamed for adverse reactions simply because underlying conditions went undiagnosed, noted Dr. Bielsker of Solvay Animal Health. "There are many reasons why an animal may occasionally become ill after vaccination, most of which are not directly related to the vaccine that was used," Bielsker said. "Often, the animal may have had an underlying condition, such as kidney disease or heart disease, at the time of vaccination, which causes it to become ill. However, the public may only hear bits and pieces of what happened, and the true cause of the problem is oftentimes never communicated. Am I saying that vaccines themselves are never to blame for complications that may occur? No. What I am saying is that, in my experience, it is very rare." As for the assertion that vaccination may lead to chronic illnesses, many outside the holistic community find the notion a tough concept to swallow without further proof. "These are very difficult questions. The problems these people report are so vague they almost defy typical scientific efforts to investigate," said Dr. David Hustead. "The data is not there at this time to back up the contention [that vaccines may cause low-grade, chronic illness]," agreed Philip Kass, D.V.M. Ph.D., a researcher with the Department of Population Health & Reproduction at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California at Davis. "I'm not saying it's false, but I'm not saying it's true either. I just don't think the hard evidence is there yet." "The immune system puts computers to shame [in complexity]," cautioned Dr. Schwartz. "The simple answers are always the easy ones, but they're almost always the wrong ones." Many holistic veterinarians, however, remain convinced that the connection between vaccination and other animal health problems is real. "It's happened often enough to make us feel, sure enough, [it's true]!" said Dr. Blakey. "But not often enough to make the 'scientific' community accept our interpretation as completely valid. Because it is observation. And that's not a scientific study." Other Reaction Risks: While there's no proof positive at present of a link between vaccination and chronic illness, it is accepted that vaccines do sometimes cause what are termed 'acute' reactions in a small number of cases. Within a few minutes or hours after the injection, an animal may develop swelling at the site, fever, vomiting, anaphylactic shock, or even seizures. Left untreated, the animal may die. The risk that an animal will have a severe reaction to a vaccine is extremely small, experts emphasize. "For vaccines to be licensed, they must meet USDA standards to show they are safe and protective at or above a given threshold level," explained Dr. Schwartz of Hoechst Roussel. "Generally, only fractions of one percent of animals will respond adversely." Just as a small percentage of humans experience life-threatening response to a bee-sting, an animal's response to a particular vaccine depends on the individual's own unique chemistry. "You and I can both receive the same vaccine, and you may not have a problem at all and I may start breaking out in hives," explained Dr. Beth Bielsker of Solvay Animal Health. "Does that mean the vaccine is bad? I don't think so. Your immune system processed it normally and mine sort of superprocessed it." There is also a small risk that vaccinated animals may not be adequately protected against the disease for which the vaccination was given, acknowledged Dr. Schwartz of Hoechst Roussel. "Vaccines don't have to be 100% protective, or we wouldn't have any vaccines because there's nothing foolproof," he noted. "Generally, the efficacy rate is well above 90%, but in some cases it may be in the 80% range. The degree of protection is a function of the nature of the vaccine, the nature of the disease it protects against, the length of time since the last exposure to the vaccine or disease agent, and the individual animal's ability to develop a protective response, once immunized." Recent research has also linked certain feline vaccines with injection-site fibrosarcomas, a type of cancer. "Our research confirmed that there was a relationship between giving vaccines and developing tumors in cats," said Dr. Philip Kass. Two vaccines seemed to be causing it the most: feline leukemia and rabies, [regardless of the brand being given]. We also found that cats that had received multiple injections in the same place had a higher risk than cats with only one vaccination there." But despite the link with vaccines established by his research, cat owners should not jump to con-clusions, Dr. Kass cautioned. "Not all vaccines cause fibrosarcomas, and not all fibrosarcomas are caused by vaccines," he emphasized. Breed-Specific Reactions: You may have heard that purebred animals are at greater risk for developing an acute vaccine reaction. Is that true? Absolutely," noted researcher Dr. Ronald Schultz. "But what's even more true is that certain families, certain lines of genetics within a breed are more susceptible than others. It's not a simple Mendelian thing, however --it's multi-genic and highly complex. So one parent could have [a vaccine sensitivity], and the progeny could still be without it." Among dogs, breeds at highest risk of having an adverse vaccine reaction include Akitas, Weimaraners, and harlequin Great Danes, noted Dr. Jean Dodds. "[These breeds] have highly genetically predisposed blood lines," she explained. That is, within the breed, there are very commonly bred lines that apparently have this susceptibility." In addition, some individual animals within a certain breed may produce a lesser immune response to a vaccine than others. "Clearly, all dogs within a particular breed --rottweilers are prominent examples -- simply don't respond equally to vaccines; some dogs may not seroconvert (i.e., develop antibodies in response to vaccination) until two years of age or older," said Richard Ford, D.V.M., a professor of medicine at the College of Veterinary Medicine at North Carolina State University. "And of greater concern, we know that immunization failure is more likely to be the result of the individual's inability to respond to the vaccine than it is a failure of the vaccine's ability to immunize." Such breed-specific results are understandable, noted Dr. Schwartz of Hoechst-Roussel. "There is a thing called hybrid vigor; the hybrid mongrel animals in this world tend to have fewer quirks when it comes to [responses to vaccines] than purebreds," explained Dr. Schwartz. "That's because their family tree is a forest. When you breed in certain traits, here may a whole lot of other things thrown in, including insufficient immune responses. That's one of those trade-offs [in buying a purebred animal]." Conclusion: The wisdom of current vaccination protocols -- especially of annual revaccination for every animal -- is clearly being called into question. And in Part II of this story, we'll take a look at what some experts are recommending as alterna-tives. But even some of the most outspoken critics of the way we currently vaccinate our pets stress that their position should not be misconstrued. "There have been so many things said recently about vaccines in a negative context that I'm beginning to worry now that we have animal owners who are very confused, and some are very scared," emphasized Dr. Schultz. "Animals shouldn't necessarily be vaccinated every year -- it's something I've stated since 1978. But some folks who are into holistic veterinary medicine have taken the view that you don't need any vaccines, and [in my opinion] that's absolutely not correct." "Everything sort of has its day, things come and go, wax and wane," points out Dr. Carvel Tiekert. "Are people over-reacting? I don't know. In my own opinion, perhaps a little bit. But then, American society has never done real well staying in the middle." Clearly, the issues are difficult ones; there are no easy answers. But there are many good sources of information. Perhaps the best place to begin is by talking about the issue of vaccination with your own veterinarian. "Maybe it's worth discussing it with two veterinarians to try to get a point-counterpoint," suggested Dr. Schultz. "And I can assure you, if you discuss this issue with both an allopathic and a homeopathic veterinarian, they will have a view and counterview for you." "I would encourage everyone to be really persistent consumers," advised Dr. Blakey. "I want them to keep their brain cells plugged in, ask hard questions, and ask them from more than one source. There are some wonderful books out there -- pick them up and read them. It's a whole education thing." SIDEBAR I VACCINES: A Short Primer: Edward Jenner probably had no idea he was spawning a medical revolution when he inoculated an eight year old boy with the relatively benign cowpox virus in 1796 and then confirmed the boy's immunity to smallpox. But the principle used by this observant British country doctor has led to the development of today's human vaccines for diptheria, polio, whooping cough, and measles, as well as animal vaccines against rabies, distemper, parvovirus, and other diseases. Vaccines are produced by taking a virus or other disease- causing agent (known as a pathogen), and either killing it or rendering it less dangerous by culturing it under prescribed conditions in a lab. These killed or "modified-live" organisms (known as antigens) are then incorporated into a vaccine solution. "Killed" vaccines may also include chemicals known as "adjuvants" which help to enhance the immune-producing action of the vaccine. "When injected with a vaccine, the animal's immune system is forced to create a response-- just as if they had been exposed to the disease," explained Dr. Hustead of Ft. Dodge Animal Health. " Through the process of creating this response, they learn how to deal with the more pathogenic versions of the same organism." There is significant con-troversy in the medical community about which type of vaccine is preferable -- a "killed" or a "modified-live". Typically, modified-live vaccines require a lower concentration of antigens and produce a longer-lasting immunity than a killed vaccine. However, because a modified-live vaccine contains live (if attenuated) organisms, there is a remote but real pos-sibility that these organisms can mutate into a disease-causing form. Killed vaccines avoid this potential risk, but often must be administered several times to produce an adequate immune response. In addition, the adjuvants incorporated into some killed vaccines may themselves be responsible for adverse reactions in some animals. Scientists are also showing increasing interest in "recombinant" vaccines, which use only a genetic fraction of the disease-causing organism -- enough to stimulate an immune response, without the remainder which is responsible for causing the disease. Researchers hope that these new technologies will prove even safer than today's vaccines, while offering equal or better protective results. SIDEBAR 2: Reporting An Adverse Reaction: What should you do if your pet suffers a vaccine-induced reaction? If the emergency happens at home, your first call, of course, should be to your veterinarian. Aferwards, however, reporting the problem may help other pet owners avoid a similar ordeal. According to Brian J. Erdahl, D.V.M., senior biologics specialist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Biologics Hotline, owners of pets who experience a negative reaction to any vaccine should promptly notify both the Biologics Hotline and the manufacturer of the vaccine. "We get reports from consumers, from universities, from veterinarians through the AVMA's Practitioners' Reporting Network, and occasionally by referral from the FDA," Dr. Erdahl explained. "We are the ones that compile that data, and we keep a database of reports on products." Not every adverse reaction is considered indicative of a problem with the vaccine itself, Erdahl noted. "We expect a certain amount of reactions; it's just inevitable," he said. "When we get nervous is when one person gives us information on a reaction to a particular product, and the next day we get a report with the same information, from the same batch. Then we say, is this something going on with the product, or is this the baseline reaction we expect? If we think a product may have a problem, we can and will require [additional] testing of the product." Consumers may contact the USDA Biologics Hotline toll-free at (800) 752-6255. A specialist will ask you the name of the vaccine, the manufacturer, and the lot number of the product. Pet advocates also recommend making sure that your pet's adverse reaction and vaccine information (including manufacturer and lot number) are clearly noted on your veterinarian's chart. ************************************ Karin Schumacher Vaccine Information & Awareness (VIA) 792 Pineview Drive San Jose, CA 95117 408-966-9388 (phone) 408-554-9053 (fax) via@eden.com (email) http://www.eden.com/~via (website) ************************************* We Must Have The Freedom To Choose & Respect Everyone's Choice |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

© 2010-2016 Shiba-Inu-Breeders.com • All Rights Reserved • www.Shiba-Inu-Breeders.com Fair Use Notice: This site may contain copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owners. We believe that this not-for-profit, educational use on the Web constitutes a fair use of the copyrighted material (as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law). If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. |

|||||||||||||||||